There was a time in American history when black, white and brown banded together to make life better for communities in need. This was so frightening to the power elite, they had to kill it.

By Dr. Edward DeVries

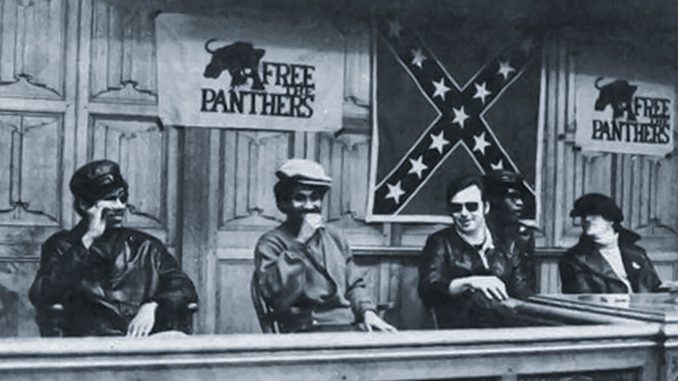

In 1969, the Black Panthers hosted a national meeting in Oakland, Calif. They called it a “Conference for a United Front,” and it attracted activists from numerous radical groups across the country. Speakers at the conference included representatives from the Communist Party USA, the Farm Workers Union, Students for a Democratic Society, the Young Patriots Organization (YPO) and, of course, the Black Panthers.

The speaker from the YPO, William Fesperman, was an interesting fellow: He wore dark glasses, a military jacket, a beret and a belt buckle with crossed pistols and a Confederate battle flag. Both the jacket and the beret also had Confederate flag patches on them. Though a resident of Chicago, Fesperman spoke with a heavy, drawling Southern accent. The Young Patriots he represented were dislocated Southerners and Border Staters—many from coal country in West Virginia and Kentucky—who had migrated to Chicago to find work in the mills, only to end up unemployed and living in a northside ghetto commonly referred to by the city’s southside blacks and westside Hispanics as “Hillbilly Harlem.”

The speaker from the YPO, William Fesperman, was an interesting fellow: He wore dark glasses, a military jacket, a beret and a belt buckle with crossed pistols and a Confederate battle flag. Both the jacket and the beret also had Confederate flag patches on them. Though a resident of Chicago, Fesperman spoke with a heavy, drawling Southern accent. The Young Patriots he represented were dislocated Southerners and Border Staters—many from coal country in West Virginia and Kentucky—who had migrated to Chicago to find work in the mills, only to end up unemployed and living in a northside ghetto commonly referred to by the city’s southside blacks and westside Hispanics as “Hillbilly Harlem.”

Fesperman and his YPO, along with Chicago’s southside Black Panthers, were among the founders of the city’s Rainbow Coalition, a name and an idea that Jesse Jackson would famously appropriate more than a decade later.

Before Jackson and the modern-day Democrats had determined upon the path of identity politics, the Rainbow Coalition was the embodiment of the idea that disfranchised people of all races, whether white, black, brown, red or yellow, could work together to create a new society that would benefit every group—the exact opposite of the political model employed by the “Rainbow Coalition” and left-wing politicians of today.

In the 1970s through the 1980s, the Chicago this author grew up in was a very segregated city. Poor whites lived in the north suburbs, poor blacks on the southside, and the browns—Hispanics—were found on the westside.

Over a decade after the federal courts had allegedly “desegregated” the Chicago public school system, the schools still remained segregated in practice. I attended an ostensibly “desegregated” elementary school that was still demonstrably segregated. This was achieved by assigning white teachers to teach white students, black teachers to instruct black kids, and Hispanic teachers were assigned to teach Latinos.

One day, when I was in either the first or second grade, a black kid transferred to our school in mid-year and was mistakenly assigned to a white classroom. By the next day, I was one of only a few white kids whose parents hadn’t pulled us from class. Eventually, the principal assured the parents that the black boy had been moved to an “appropriate” class.

Chicago’s neighborhoods were not just segregated by race, they were segregated by ethnicity, as well. In other words, the blacks divided into neighborhoods for Jamaicans, Africans, Creoles, Haitians etc. Likewise, the Hispanics were divided as Mexicans, Puerto Ricans, Cubans, Colombians, Peruvians, Brazilians, Hondurans etc.

Even the whites divided into neighborhoods for Poles, Italians, Frenchmen, Serbians, Gypsies, Germans, Greeks, Brits, “hillbillies” etc.

An Italian would probably sooner have a black family move into the neighborhood than a Polish one. The same was true of other races as well. For example, the Mexicans and the Puerto Ricans never mixed.

“Hillbilly Harlem” was actually a slum, densely populated with poor whites who had migrated north after WWII, primarily from Appalachia. Their neighborhood had a culture that was very different from that of the other whites in Chicago because they displayed Confederate battle flags in their taverns, and country music spilled out of their jukeboxes.

Hy Thurman and his older brother Rex grew up in Dayton, Tenn. In 1967, they dropped out of high school and hitchhiked to Chicago to find jobs. When they couldn’t find them, they sold their blood to blood banks for cash. Eventually, they found work as day laborers.

They also joined a street gang called the Goodfellows, which soon joined forces with a community organization having the acronym “JOIN” (Jobs or Income Now) that demonstrated for housing and welfare reform by fighting Mayor Richard Daley’s political machine and the Chicago police.

Organizing against police brutality was a top priority for the Goodfellows because their members were constantly stopped by police and subjected to unlawful searches and sometimes even beatings. One day, the police raided JOIN’s office that was located in a church sympathetic to their efforts. A police officer shot an unarmed Goodfellow in the back as he was running away.

This senseless act of murder by Chicago’s “finest” was the catalyst for the Goodfellows, JOIN, and other groups of “hillbillies” to join forces and organize into what came to be known as the YPO. The YPO proudly proclaimed itself to be “by and for hillbillies.” The group was very organized. They were formally constituted, elected leaders, drafted an 11-point program and adopted the Confederate battle flag as their official symbol.

The Thurman brothers recruited new members from among all of Hillbilly Harlem’s pool halls, taverns and honky-tonks. In his recruiting efforts, Thurman encountered Bob Lee of the Illinois Black Panther Party, who quickly realized that he and Thurman—though working in different sides of town and among different races—were essentially fighting the same foe and doing so with similar tactics.

Thus, in the fall of 1968, Lee invited Thurman to join him to address a mostly white Methodist church where Lee was scheduled to speak to a group of white, middle-class liberals who were curious about the non-militant side of the Panthers. At Lee’s request, Thurman also gave a presentation on the efforts of the YPO.

While the audience treated the black Lee as a curiosity, they were openly hostile to the white Thurman. (Recall how I earlier remarked that a white in Chicago would prefer to have a black move into his neighborhood than another white of the wrong ethnicity?) The liberal middle-class whites were far more tolerant of Lee’s Black Panthers than they were of Thurman and his hillbilly patriot group.

Lee could not believe what he saw and heard. He watched middle-class whites attack poor whites with a brutality that even the ethnically and economically segregated blacks would have never let loose upon one another. Lee rose to Thurman’s defense at the meeting, and afterward suggested that the two groups join forces.

Initially, Fred Hampton, the chairman of the Illinois Black Panthers, expressed strong opposition when Lee formally proposed the unification at a Panther meeting. But after a few weeks of observing Thurman and the YPO, Hampton and the rest of the Panther leadership became enthusiastic about the merger.

It was then that they christened their alliance “the Rainbow Coalition.” The Panthers even voted to adopt the YPO’s symbol—the Confederate battle flag—after merging it with their black fist symbol. The YPO had never considered the battle flag—or as they called it, “the Rebel flag”—as a symbol of racism. They called it “the Rebel flag” because they saw it as a symbol of rebellion. The Panthers thought of “the Rebel flag” in exactly the same way.

Under the banner of the Rebel flag, the Rainbow Coalition grew to include the Young Lords, a radical Puerto Rican group. Together, the blacks, whites and browns held citywide unity rallies speaking out for police reform and against poverty. They held rallies in places like Grant Park and occupied government buildings to demand better health care and housing.

Gang members from all races were drawn to the coalition. They eventually organized their own neighborhood clinics and social services. Even the American Indian communities began to join them, and they started a free breakfast program. Then the middle-class whites started to join groups dedicated to helping the poor.

When that happened, Mayor Daley began to see the coalition as a rival to his political machine. He had the police shut down the free breakfast program and ordered the health department to close their neighborhood health clinics. The FBI also infiltrated the group and immediately began to sow seeds of discord that would tear apart the interracial coalition.

Just five months after their big meeting in Oakland—on Dec. 4, 1969—the Chicago police conducted a pre-dawn raid of Fred Hampton’s home and, in the process, murdered the leader of the Panthers. This sent Thurman and other coalition leaders into hiding.

Fesperman broke away from the coalition, moved to New York and formed a political party he called the Patriot Party. After he established offices up and down the East Coast, the feds raided his New York office and other offices, effectively ending the enterprise.

Shortly thereafter, the Chicago police chief accused the YPO of conspiring to detonate a bomb and arrested much of its leadership. They even arrested people from allied churches and community groups as co-conspirators.

Still, the Rainbow Coalition persevered, eventually defeating the Daley political machine in 1983 when they succeeded in electing Harold Washington as the city’s first black mayor.

Jesse Jackson declared himself the leader of the Rainbow Coalition in 1984, using it to launch his insurgent presidential campaign. He would ride the coalition wave all the way through his nearly successful 1988 run.

David Axelrod, who would later serve as chief of staff to Barack Obama, drew on what he learned as a Rainbow Coalition activist when he managed Mayor Washington’s 1987 reelection campaign. He would retool the same tactics in 2008 to maneuver Obama into the Oval Office, though many insist Obama was ineligible.

But as modern Democrats like Jackson, Axelrod and Obama (the “community organizer”) took over the Rainbow Coalition—even using its strategy and methods—they discarded the coalition’s appeals to racial unity and class solidarity, replacing them with rigid racial identity politics. And, of course, they tossed aside the banner under which all of the races had united in the original coalition: the Confederate battle flag.

A pastor and traveling speaker, DR. EDWARD DEVRIES is the editor of the Dixie Heritage Newsletter and a contributing editor to TBR. He is also the host of TBR’s radio show in which Ed interviews not only members of the TBR staff, but also some very well-known guests. For more, see TBR’s website www.BarnesReview.org. Click on the Radio tab on the menu.

This article was originally published in the July/August 2019 edition of THE BARNES REVIEW, a politically incorrect history magazine that is not afraid to discuss subjects that are completely taboo in today’s historical and political climate. To subscribe, call 1-877-773-9077 toll free, Mon.-Thu. 9-5 ET. The cost is just $56 in the U.S. for one year—six big issues—packed from cover to cover with authentic, uncensored information on all periods of world history.