There’s a problem in the U.S. executive branch and the Oval Office that has for decades led to nearly unlimited freedom for the “unitary executive” to make whatever decisions are desired without congressional approval.

By S.T. Patrick

In the wake of the Mueller report, Congress has continued its debate on the definitions and limitations of “executive privilege.” The national security establishment, a powerful arm of the executive branch, has pushed further toward a military conflict with Iraq, and America’s armed forces continue to be stretched worldwide for purposes that become less clear by the day. The role of the nation’s chief executive has moved further down the rabbit hole that historian Arthur Schlesinger Jr. once called “The Imperial Presidency.”

Schlesinger wrote the monumental work in 1973 to analyze the transformation of the presidency over its first two centuries. Schlesinger’s premise was two-fold: first, that the presidency, then in Nixon’s final year, was out of control, and second, that the presidency had far surpassed its constitutional limitations. The book was often updated, and its final version continued through George W. Bush. Today, historians and political scientists are rightly wondering what the presidential limitations are and when a presidency has propelled itself over a constitutional cliff.

In a June 8, 2019 memo to the Justice Department, Attorney General William Barr proposed his interpretation that a president’s power over the executive branch can only be limited in two very distinct, constitutional ways: The voters can limit a president by voting him from office, and Congress can limit the executive authority held by a president through impeachment power. Thus, theoretically, a president who wins re-election and escapes impeachment could still have acted improperly but would still be above the law.

This idea of a nearly omnipotent presidency—academically called the “Unitary Executive Theory”—is not directly stated in the Constitution itself. Article 2 does vest the executive power of the country in the hands of the president, but it does not specifically state the limitations thereof. The term was first used by Reagan Attorney General Ed Meese. Attorney General John Yoo later adopted it as a constitutional basis for the more sketchy aspects of Bush’s torture program.

Presidents have certainly taken questionable, unitary steps for much of the 20th century. President Harry Truman bypassed the congressional power to declare war by entering the U.S. into a “police action” in Korea. The precedent extended to conflicts in Vietnam, Nicaragua, Grenada, Panama, Kuwait, Iraq, Afghanistan, Libya, and Syria. President Trump may soon extend the precedent into Iran. President Nixon set up a secret national security establishment that would report only to him and only in private, thus bypassing congressional committees along with the State and Defense Departments.

In more recent years, President Barack Obama used drones to take the lives of U.S. citizens abroad without the policy going through a public congressional inquiry process. The current means by which presidents have assumed power has been via executive order. President Clinton signed 254 executive orders, Bush signed 291, Obama signed 276, and, thus far, Trump has issued 111.

While Alexander Hamilton was the first founder to argue for a strong executive, debate about an executive council (rather than one, single executive) continued throughout the Constitutional Convention in 1787. There was fear that having a single executive, a president of the United States, would over time resemble a monarch. When looking at the growing power of the late executives, before and through Trump, it is difficult to say the founders weren’t prescient.

When a president extends his power beyond that which was allowed for by the Constitution or envisioned by the founders, questions of morality and legality inevitably exist. Schlesinger questioned the growing imperial presidency and argued that it was faulty when the president lacked a Washingtonian sense of virtue. This idea of being “above the law” was never explained more coherently and directly as when Nixon, in the aftermath of Watergate, told famed interviewer David Frost that “when the president does it, that means it’s not illegal.”

A problem also exists within the executive branch itself. As we approach a time when the branch and its offices are more powerful than the Oval Office, an all-powerful executive branch, absent from the media scrutiny that befalls a president, becomes its own uncontrollable Beltway behemoth.

American Free Press has long argued that presidents and their executive branch appointees are not above the law, regardless of party affiliation. Trump’s incessant revolving door of hawkish appointees and neoconservative advisors already has an appearance of an executive who is fishing the swamp rather than draining it. But that’s tame compared to what a limitless executive can enact in the cause of war. In saying a collective rosary for a Mueller prosecution, Congress was always looking awry. There is a structural problem that has continued to grow at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue for over a century.

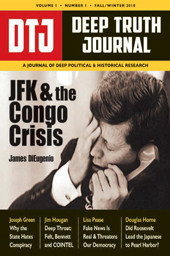

S.T. Patrick holds degrees in both journalism and social studies education. He spent 10 years as an educator and now hosts the “Midnight Writer News Show.” His email is [email protected]. He is also an occasional contributor to TBR history magazine and the current managing editor of Deep Truth Journal (DTJ), a new conspiracy-focused publication. DTJ’s 132-page inaugural Fall/Winter 2018 edition is available from the AFP Online Store.

Congress has “progressively” abdicated much of their legislative power to the Executive, especially in the 20th century, even as that legislative power has far transcended the Constitutionally enumerated powers of a central gum’ment.

If the Legislature had confined their function to that which the Constitution limited them, Executive privilege to the extent it is used today would not be necessary, or possible.