In a new book, journalist Mark Feldstein claims Nixon and his men desperately wanted to get rid of renowned columnist Jack Anderson, who Nixon blamed in part for his loss to JFK in 1960. They considered an assortment of ways to silence Anderson’s criticisms of Nixon and his administration, from criminal prosecution to defamation of character to outright murder.

By S. T. Patrick

The common factors that drove columnist Jack Anderson and President Richard Nixon to the apex of their respective fields are the same that tore them apart and made them adversaries for more than 25 years. The escalating tension between two of the most powerful men in Washington, D.C. climaxed in the year before Watergate, as Nixon’s men wanted Jack Anderson dead.

Anderson and Nixon were both from small, western towns. Their middle-class upbringings often made them uncomfortably conscious of the class warfare inherent within elite society. Anderson was a devout Mormon, while many of Nixon’s social leanings reflected his Quaker upbringing. Both men wrote, walked, talked, and lived like they perpetually had something to prove.

While money was not the driving factor behind the two men personally, they both placed a high value in the same Washingtonian commodity—information. They would gain it in ways that were morally and ethically repugnant to later observers and biographers. They would use it to stay one step ahead of their competition, as well as to belittle opponents who invariably attempted to agitate their most paranoid insecurities. The Beltway was a game, and they were both sore losers.

Nixon believed Anderson was partially responsible for his 1960 presidential loss to John F. Kennedy. Anderson, in his Washington Merry-Go-Round column, had printed a revelation that the Nixon campaign had secretly funneled a private donation from billionaire Howard Hughes. Anderson was in large part responsible for Nixon’s distrust of the establishment media. When the Nixon administration entered the White House in 1969, Anderson’s criticism intensified. He wrote about yet another contribution from Hughes, a favorable tilt toward Pakistan that almost caused a nuclear confrontation with Russia, a covert attempt to oust Chilean president Salvador Allende, and many other brewing scandals.

Mark Feldstein, the chair of broadcast journalism at the University of Maryland, has written Poisoning the Press: Richard Nixon, Jack Anderson, and the Rise of Washington’s Scandal Culture, which is simultaneously a biography of Anderson and a well-written account of his conflict with Nixon.

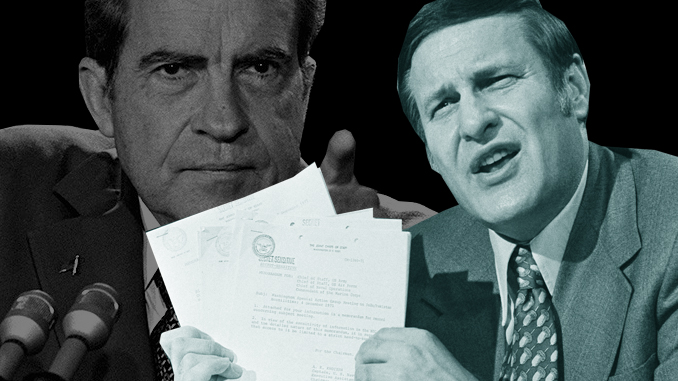

Feldstein details how Nixon’s “Plumbers”—G. Gordon Liddy, E. Howard Hunt, and company—were created to plug the leaks Anderson used to such success. At one point, Anderson’s column was syndicated in over a thousand newspapers, including The Washington Post. He was the subject of a Timemagazine cover story under the headline “Supersnoop,” he won a Pulitzer Prize in 1972, and he was featured on “60 Minutes.”

“Jack Anderson was like Ahab chasing after Richard Nixon, this great white whale, and he plagued Nixon from the very beginning of his career,” wrote Feldstein.

Nixon explored many options of what could be done with Anderson. On Jan. 3, 1972, he discussed with Attorney General John Mitchell the possibility of criminally prosecuting Anderson for publishing classified documents.

“I would just like to get a hold of this Anderson and hang him,” said Mitchell.

Nixon replied, “So listen, the day after the election, win or lose, we’ve got to do something with [Anderson].”

Liddy and Hunt met with other Nixon aides to discuss what could be done to thwart the muckraking journalist. A spy was placed in Anderson’s office where Colson attempted to plant a false White House document. They considered labeling Anderson as gay, which he was not, and charging that his legman Brit Hume was his gay lover. The administration then tried leaking information on Anderson to The Washington Post, which instead printed a story about how Nixon was trying to smear Anderson.

Exasperated, the Plumbers turned to the one method of silencing Anderson that would work permanently—murder. Hunt and Liddy, under orders from Colson, met and plotted potential ways to kill Anderson. They interviewed a CIA poison expert to determine whether they could poison him without detection. They put Anderson under surveillance to see if there was a location on his regular route to potentially stage a fatal auto accident. They staked out his home to case the vulnerable points of entry that could be penetrated to swap prescription medications for poison. The most bizarre consideration was the idea of lacing Anderson’s steering wheel with LSD, thus causing an accident.

Finally, they decided that the best means would be to stage a mugging that would end in Anderson’s death. Liddy later claimed that he had volunteered for the latter and was satisfied with breaking Anderson’s neck. Before his death, Hunt also corroborated the scheme to kill Anderson.

Colson called off the plan to kill Anderson, as the funds had been earmarked elsewhere. Six weeks later, the burglars were arrested at the Watergate complex.

When the second Watergate break-in occurred in June 1974, Chief of Staff H.R. Haldeman tried planting a story that blamed Anderson. Dating back to the 1950s, Anderson had been involved in buggings and break-ins in an effort to acquire damaging information on politicians. Making Haldeman’s plan even more potentially credible, Anderson was also friendly with Watergate burglar Frank Sturgis, who had been his house guest in Washington, D.C. In a strange turn of coincidence, Anderson ran into Sturgis at the airport on the night of the Watergate break-in. Sturgis and the burglars were flying in from Miami. When Anderson first heard about Watergate, he instantly knew who was involved.

Anderson’s later career was plagued with factual errors, dwindling readership, and an affinity for the Reagan administration that took the bulldog out of the aging reporter. Nixon would resign from office and live out his life writing about global issues. Nixon would die in 1994, and Anderson would succumb to the effects of Parkinson’s disease in 2005. He had retired his column a year before at the age of 81.

S.T. Patrick holds degrees in both journalism and social studies education. He spent ten years as an educator and now hosts the “Midnight Writer News Show.” His email is [email protected].