By S.T. Patrick

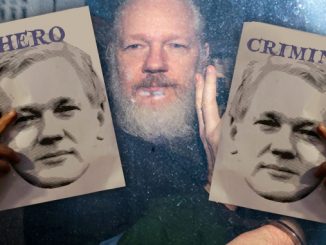

As the only non-court official in the gallery when the Julian Assange verdict was announced on Jan. 5 in England, former British Ambassador to Uzbekistan Craig Murray said, “The judgment is concerning, but we are nonetheless delighted.” Concerning it was, and still is, as 2021 has already been an important if not depressing year for freedom of the press.

Judge Vanessa Baraitser denied the U.S. request to extradite Assange, the founder of whistleblower website WikiLeaks, to face charges stemming from alleged violations of the 1917 Espionage Act. While the denial of extradition was a pleasant surprise to some, Baraitser did not release Assange immediately nor did she rebuke the request. Quite the opposite.

Baraitser accepted and confirmed the U.S. prosecutor’s case against Assange. She also validated the UK’s right to extradite for political purposes under the 2003 UK Extradition Act. While acquiescing to both the U.S. and UK federal governments, Baraitser’s motivation for denying the request in the end was a continuing, obvious yet shocking, admission about incarceration in the United States: It’s inhumane.

Assange will not be extradited to the U.S. because Baraitser deemed conditions within the U.S. federal supermax prison structure to be rife with structural and psychological inhumanity. Behind the maximum-security walls are an America most residents never see. Prisoners are allowed little to no human contact, even with guards. The cages that house the prisoners are abnormally small, and the “exercise areas” in which a prisoner is allowed one hour per day, alone again, are also abnormally small. Many remain in this inhumane, psychologically drenching isolation for decades. Baraitser cited Assange’s deteriorating health as a leading factor in her decision to deny extradition.

In a 132-page ruling, Baraitser declared, “Faced with the conditions of near total isolation without the protective factors which limited his risk at [Her Majesty’s Prison] Belmarsh, I am satisfied the procedures described by the U.S. will not prevent Mr. Assange from finding a way to commit suicide, and for this reason I have decided extradition would be oppressive by reason of mental harm, and I order his discharge.”

Chris Hedges, the host of RT America’s “On Contact” program, wrote, “The publication of classified documents is not yet a crime in the United States. If Assange is extradited and convicted, it will become one. The extradition of Assange would mean the end of journalistic investigations into the innerworkings of power. It would cement into place a terrifying global, corporate tyranny under which borders, nationality, and law mean nothing. Once such a legal precedent is set, any publication that publishes classified material, from The New York Times to an alternative website, will be prosecuted and silenced.”

Baraitser denied extradition, yet Assange was not yet free. The U.S. prosecutors declared that an appeal will take place. Assange is still at risk. Later in the week, Baraitser denied Assange bail and refused to discharge him while the U.S. makes its case for appeal. He was instead ordered to return to Belmarsh prison, one of the UK’s harshest incarceration facilities.

Assange’s defense had argued to Baraitser that he should be placed under house arrest with his partner Stella Morris and their two sons. While under house arrest, Assange volunteered to wear an ankle monitor. Baraitser denied the defense’s request, claiming she was “satisfied that [Assange] might abscond.”

Assange’s attorneys will appeal the decision to deny him bail.

There is a lot at stake in the Assange ruling. Global freedom of the press is on the line. Independent journalists like Jonathan Cook know all too well the price that Assange has paid and the obligation that we now have.

“Assange’s battle to defend our freedoms, to defend those in far-off lands whom we bomb at will in the promotion of the selfish interests of a Western elite, was not autistic or evidence of mental illness,” Cook wrote. “His struggle to make our societies fairer, to hold the powerful to account for their actions, was not evidence of dysfunction. It is a duty we all share to make our politics less corrupt, our legal systems more transparent, our media less dishonest. Unless far more of us fight for these values—for real sanity, not the perverse, unsustainable, suicidal interests of our leaders—we are doomed. Assange showed us how we can free ourselves and our societies. It is incumbent on the rest of us to continue his fight.”

Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison said Assange is “free to return home” if the U.S. appeal fails. Because the United States may choose to extradite him from most other countries, Assange may not find safety anywhere else but his home country. For the whistleblowing publisher of the “Iraq War Logs”—that proved that the American military had engaged in a bevy of incredible atrocities—there will truly be no place like home.

S.T. Patrick holds degrees in both journalism and social studies education. He spent 10 years as an educator and now hosts the “Midnight Writer News Show.” His email is [email protected]. He is also an occasional contributor to TBR history magazine and the current managing editor of Deep Truth Journal (DTJ), a new conspiracy-focused publication available from the AFP Online Store.