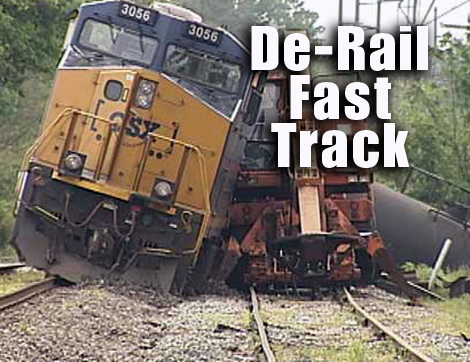

• America needs to slow track trade deals, not fast track them.

By Leo W. Gerard —

In close votes in June, a majority in the U.S. House and Senate chose to continue glomming onto the same tired, old, broken-down trade tactics that have closed American factories, cost American jobs and caused massive trade deficits.

The majority voted to sustain for the next six years trade policies that failed American workers for the past 20. The majority abdicated Congress’s constitutional responsibility to supervise international trade. Instead, they agreed to allow presidential administrations to once again negotiate trade deals in secret, then whip those corporate-appeasing, clandestine schemes through the congressional approval process with absolutely no amendments, no changes, no improvements.

That’s the “fast track” process under which Congress has averted its eyes and approved one job-killing, deficit-ballooning trade deal after another, starting with the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) in 1994. The result of that indolent, duty-shirking process since then has been 57,000 shuttered American factories and 5 million lost jobs.

Now, instead of conceding failure and forging a new path on trade, the House and Senate cleared the way to destroy more American manufacturing and family-supporting jobs.

These backward-facing lawmakers would benefit from stepping out of lobbyist-infested D.C. and speaking to small-town manufacturing workers who lost their livelihoods because fast-tracked free trade schemes encouraged corporations to offshore factories.

Maybe these pro-trade deficit politicians should listen as American steel, paper and tire workers describe what happened to them and their families and their communities when fast-tracked trade schemes pitted them against child workers and forced laborers in foreign factories.

Maybe those politicians should hear formerly middle-class workers tell of unenforced provisions in fast-tracked free trade schemes that enable foreign manufacturers that violate international trade regulations to steal market share from American businesses.

They should, for example, pay attention to Kori Sherwood.

When she got a job two years ago as a millwright at U.S. Steel’s Minntac facility in the Minnesota Iron Range, it changed her life and that of her young daughter. But in March, U.S. Steel sent layoff notices to 680 of Minntac’s 1,500 workers, citing an international glut of steel. Prices are at a 12-year low as mills in China continue to produce and ship massive amounts of steel and sell it below market prices made possible by improper government subsidies and support.

Under international trade law, countries can prop up industry with government subsidies when the products are sold internally. Beijing may give its steel industry no-interest loans and free electricity when the rebar or pipe or I-beams are sold for construction projects in China. But international trade law forbids such subsidies when the goods are sold internationally because government aid suppresses product prices in what is supposed to be a free market. Some countries, however, routinely flout the rules. Then American companies that don’t get no-interest government loans or free electricity or other subsidies can’t compete on price.

They shut down mills and lay off workers. Unions and manufacturers are forced to pay millions to petition for import duties on the subsidized foreign goods to level the playing field. To win such a case, industry must prove financial injury and workers must suffer layoffs and lost income.

Ms. Sherwood got one of U.S. Steel’s layoff notices and lost her job at Minntac on May 26. China’s violation of international trade rules dashed Ms. Sherwood’s hopes and plans.

“You finally think you get your life in order—buy a truck, buy a home—and it all falls apart,” she said.

My union, the United Steelworkers (USW), has repeatedly petitioned for trade law enforcement. In too many cases, however, decisions arrive so late that factories are permanently closed and workers seriously scathed.

Fast-track-loving lawmakers should talk to American workers who once made uncoated paper, the non-shiny stuff used in copy machines. The USW and four American paper companies filed a trade case in January because tons of improperly subsidized paper from Australia, Brazil, China, Indonesia and Portugal were crushing American uncoated paper manufacturers.

Companies in these five countries kept their mills running and their workers employed by dumping illegally subsidized and underpriced paper into the U.S. market. These trade scofflaws bankrupted American paper mills and paper workers.

Since the dumping began in 2011, two U.S. companies that manufactured uncoated paper went out of business and a third stopped making the paper. Two firms closed two uncoated paper mills. Three others shut down four machines that produced the paper. The human cost of this: 2,500 family-supporting American jobs destroyed.

Communities suffer as well.

In March 2014, International Paper permanently shuttered its 43-year-old uncoated paper mill in tiny Courtland, Alabama. It was the area’s largest employer. More than 1,100 workers lost their jobs. Suddenly gone was an annual payroll of $86 million and $2.3 million in tax payments that the town, county and schools depended on every year.

Four of the uncoated paper mills applied for Trade Adjustment Assistance, a federal program that retrains workers if it can be proved that they were sacked because of international trade. All four qualified. That helped. But it did not restore good, family-supporting union manufacturing jobs.

Import-adoring lawmakers should talk to tire builders from Tuscaloosa and Gadsden, Alabama, Findlay, Ohio, and Salem, Virginia, who have watched with endless anxiety over the past decade as American manufacturers closed plants and cut production because Chinese producers dumped subsidized passenger and light truck tires into the U.S. market.

After the United Steelworkers Union (USW) petitioned for relief, the U.S. imposed import duties on Chinese tires beginning in 2009 and imports declined significantly. American producers regained market share and invested in American factories. They recalled laid off workers and even hired new ones.

But the second the duties expired, Chinese producers resumed dumping. American companies once again cut production, reduced workers’ hours and furloughed staff. The USW petitioned for trade relief again a year ago, and the Department of Commerce imposed preliminary duties. Since then, U.S. tire companies have ramped up production and increased workers’ shifts.

In testimony earlier this month before the U.S. International Trade Commission seeking permanent duties, David Hayes, president of the USW local union at Goodyear’s tire plant in Gadsden, talked about how the waves of dumped foreign tires have denied his fellow 1,500 workers job stability as layoffs followed each import surge.

Since the preliminary duties, Goodyear has added new tire machines and hired 188 workers. But if the duties disappear, Hayes fears his plant could suffer the fate of the factory Goodyear closed in Union City in 2011. He told the trade commission that would devastate workers’ families and the state, to which the plant annually contributes $360 million in direct and indirect economic activity.

American workers and American manufacturers don’t oppose trade. They can compete on a level playing field with anyone in the world. But the current trade regime, swept in without serious analysis on the back of fast-track authority, has failed to provide a level playing field.

America needs a new vision for trade. And to achieve that, lawmakers must slow-track proposed trade deals.

Leo W. Gerard also is a member of the AFL-CIO Executive Committee and chairs the labor federation’s Public Policy Committee. President Barack Obama appointed him to the President’s Advisory Committee on Trade Policy and Negotiation and the President’s Advanced Manufacturing Partnership Steering Committee 2.0. He serves as co-chairman of the BlueGreen Alliance and on the boards of Campaign for America’s Future and the Economic Policy Institute. He is a member of the executive committee for IndustriALL Global Labor federation and was instrumental in creating Workers Uniting, the first global union. Follow @USWBlogger.