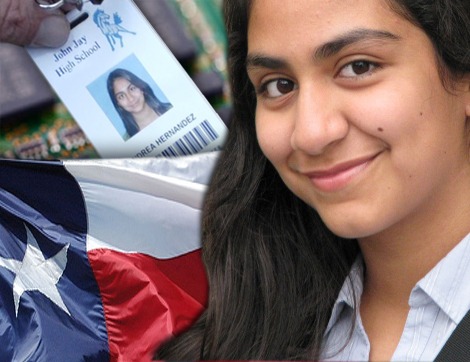

• You can beat Big Brother: Student Andrea Hernandez inspires peers, parents, people across the world

By Mark Anderson

In a dramatic development, the huge Northside Independent School District (NISD) in San Antonio, Texas announced July 16 it was scrapping its widely distrusted program of microchipping student IDs with radio frequency identification (RFID) technology—which brave NISD student Andrea Hernandez opposed with all her might. With unwavering support from her father, she sparked a groundswell that overcame the NISD administration’s designs.

“Oh thank you, Jesus,” an elated Andrea exclaimed during the July 16 broadcast of this writer’s weekly radio show “Beyond Exposure,” one of several shows featuring AFP writers and editors on the new AMERICAN FREE PRESS RADIO NETWORK.

AFP readers first heard about Andrea’s situation last fall, when this newspaper broke the story nationally. When asked about the NISD’s decision to drop the forced microchipping program, Steven, her father, almost at a loss for words, replied that as recently as a few weeks ago, he was “in a dark valley” and victory seemed worlds away.

“Now, it’s become a worldwide movement,” he stressed. He plans to assist concerned Americans who have contacted him from Florida, Louisiana and Pennsylvania, as they confront their own student surveillance programs.

The Hernandez family’s battle started just as the 2012-13 school year began, when the NISD announced this so-called pilot program, with a rather stiff start-up cost of $525,000 and about $140,000 per year to maintain it, at just two schools: Anson Jones Middle School and John Jay High School. Andrea, on the basis of her devout religious liberty and privacy concerns, made the pivotal decision, as a John Jay sophomore, of refusing to wear her “chipped” badge. By January 2013, with many fellow students following her example, she was kicked out of John Jay and forced to attend a conventional high school that lacked the programs she wanted.

Critics maintain that RFID systems could expose students to savvy stalkers off campus who have the means to track the signal these microchips emit. Others believe this technology—promoted by NISD as a means to monitor students’ attendance and keep tabs on their whereabouts—gradually conditions students to see constant surveillance as a normal part of life.

Moreover, there are health concerns over constant radio-wave exposure.

In challenging the RFID program, the Hernandezes experienced frequent setbacks, including an unfavorable federal court decision. Steven’s valiant efforts at the Legislature in Austin—in hopes of passing House Bill 101 to give students in all Texas public schools the option of not wearing chipped IDs—was recently killed, at the last possible minute, after it had passed in both chambers.

Yet, in a world cursed by nonstop attempts to close the book on liberty, Andrea’s resistance caused unstoppable tremors in the NISD student body, across Texas and the nation, and even overseas.

Ultimately, freedom won out, although Steven says he’ll closely watch NISD’s future actions regarding any new RFID plans that could emerge.

For now, NISD Superintendent Brian Woods said:

“When we looked at the attendance rates, surveys of parents . . . how much effort it took to track down students and make them wear the badges, and to a lesser degree, the court case and negative publicity, we decided not to [continue] it.”

Steven would like to see the NISD administration pay back the district for the RFID fiasco by building fewer new schools, lowering taxes accordingly, and shifting some funds to pay teachers and bus drivers better. He added that had Andrea not resisted and sparked a larger rebellion, it’s his understanding that the NISD was prepared to add this RFID student-tracking system in up to nine more buildings. The NISD already has about 100,000 students, in more than 100 buildings.

Mark Anderson is AFP’s roving reporter. Listen to Mark’s weekly radio show on the AMERICAN FREE PRESS RADIO NETWORK.