The case brought by the FBI against two Iranian men and three Iranian officials for plotting to kill a Saudi Arabian diplomat in the United States looks to be a classic frame-up job in order to distract the public from ongoing problems plaguing the Obama regime.

“This is made up,” said Mostafa Abdelzadeh, editor of the U.S. desk at the Fars News Service, a popular Iranian news organ. “Even a U.S. official said there is no evidence linking these men to the Iranian government.”

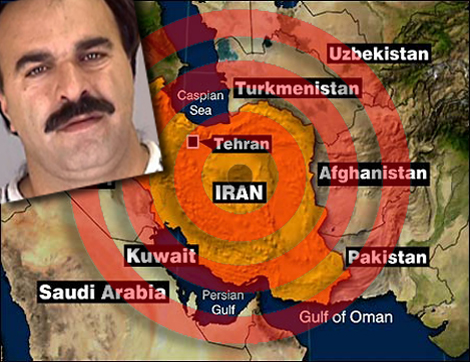

On Oct. 11, the U.S. Department of Justice announced that one of its informants, posing as a member of a Mexican drug trafficking cartel, had framed Manssor Arbabsiar, his cousin, allegedly a general in the Iranian Qods military service, and Ali Gholam Shakuri, an alleged colonel in Qods, for a “ghost terrorism” conspiracy that had been concocted by the FBI and the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA).

The DEA informant, identified in the federal indictment as “CS-1,” allegedly spoke with Arbabsiar, who had been arrested four previous times on petty charges and was likely involved in drug trafficking across the U.S. border from Mexico. CS-1 suggested that he could provide a four-man hit squad to kill a political target in the United States if he was paid $1.5 million dollars. When Arbabsiar agreed, the informant ratcheted up the charges by suggesting a bomb be used—an offense that carries a 35-year mandatory minimum jail term—and engaged in behavior that is typical of other similar FBI frame-ups of innocent Americans, including the use of the phrase “painting a house” for committing a murder—a detail that is straight out of an FBI operational manual and has been used in hundreds of similar murder-for-hire cases around the country.

During the investigation, Arbabsiar, an apparent big talker, was never able to provide the entire $1.5 million or any proof that his relationship with the Iranian government was more than just talk. Instead, according to the indictment, Arbabsiar was only able to come up with just shy of $100,000—money he used as a down payment, and which he hoped to profit from if he could receive Iranian government sanction.

Under U.S. law, the federal government is permitted to attempt to entrap any person that they believe has a predisposition to commit a crime, and can charge that person with “conspiracy” as long as one other person who is not a federal agent or informant is involved in the offense. In this case, the method of entrapment was textbook—from the use of stereotyped “code phrases” such as “to paint a house,” to the escalation of the method of attack from a shooting to a bombing, which raised the mandatory minimum sentence.

Typically, in such cases, after being framed for an act of terrorism, the victims are tortured and brutalized by the authorities until they are forced to give a false confession.

According to the indictment, Arbabsiar was beaten into giving a confession only hours after his arrest, and the only evidence definitively linking Arbabsiar to Iran is the confession he gave, which likely came under threats and torture.