By E. Stanley Rittenhouse —

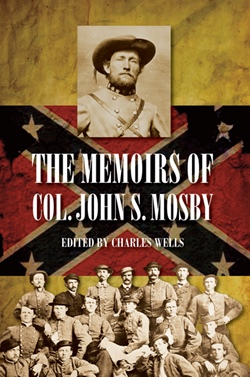

With all the furor over the “racism” and “white supremacy” of the Confederate flag, don’t be surprised if the prominent, politically-correct publishers demand a change to the cover of this book.

Better get it while you can.

Here’s his story.

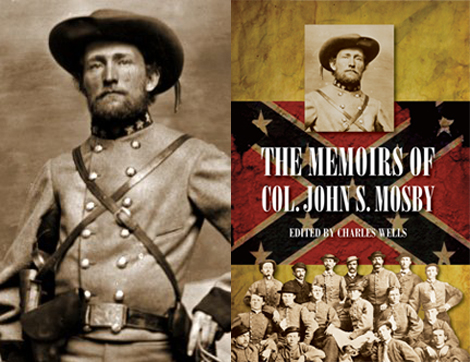

The heroic John Singleton Mosby eluded the efforts of Union troops to capture him throughout the War Against the South, earning the nickname of the “Gray Ghost.” Special counter-partisan units were organized to squash him. One such force faced off against Mosby in West Virginia. The guerrillas defeated the unit and captured its leader. At the end of the war, Mosby was one of the few Confederate leaders who never surrendered, although ordered to do so. He remains an inspiration to all patriotic young men and his tactics are studied even today.

The “Gray Ghost,” Colonel John Singleton Mosby, was a guerrilla fighter for the South and was so successful in his endeavors that if he were to be captured, he and any of his rangers were to be hanged on the spot. This reflected the fear the feds had of Mosby. He was so victorious that he tied up thousands of federals throughout northern Virginia in their terror that the United States president might be in jeopardy.

A true hero, Mosby was greatly respected among the Confederates.

With all of his exposure to danger during his many daring raids, he was never caught. However, General Robert E. Lee, who was a close friend, observed that his only fault was that he was always getting wounded—some six times.

Mosby was born December 6, 1833, in Powhatan County, Virginia and died at age 82 on May 30, 1916 (Memorial Day) in Washington, D.C. As a youngster he lived within view of Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello. He was slight of build, at 5’8” and 125 pounds, and a sickly youth.

He had a keen sense of righteousness, was ethical and fair. Throughout his life he made a distinction between the right and the wrong, and he treated the two accordingly, whether in dealing with a bully or exposing theft and corruption as a government employee.

A very intelligent gentleman, he was also a teetotaler, loved literature and was familiar with the classics.

After the war he was a highly successful lawyer. Had he not attempted to heal the gap between the North and the South by befriending President Ulysses S. Grant (the man who had put out the order that Mosby was to be hanged if caught), his financial situation would have been more prosperous. This endeavor, which reflected loyalty to his country, almost cost him his life as one good old boy of the South attempted to shoot him as he came off the train from Washington at Warrenton, Virginia.

Both Mosby and his wife, nee Pauline Mariah Clarke, were well-bred, from prominent families. When he first saw Pauline, he immediately recognized her character and quality, which included her intelligence and beauty. She gave birth eight times in 18 years and on May 10, 1876, at age 39, died in childbirth. The colonel never remarried.

Mosby’s mentor was General J.E.B. Stuart, for whom he did some scouting work early on in the war. Stuart recognized Mosby’s talent and gave him orders to form Company A, 43rd Battalion of the Virginia Cavalry, better known as Mosby’s Rangers. The initial troop consisted of nine men, which later grew to 400 rangers. He preferred young men between 17-20 years of age, for they were so willing to obey, as well as being a little naive to the danger they were about to face.

He saw the advantage of having partisan rangers, not regulars. This approach would entitle his men to the spoils of war. Many accumulated enough to buy farms at the end of the war.

And their youth never hindered their effectiveness. This reflected the leadership of their leader. Mosby’s practice was to keep the rangers in the dark about his plans until the last minute.

His choice of weapons was a Colt .44, preferring a handgun over a rifle or saber. Each ranger was to have at least two handguns; but many carried as many as four, five or six revolvers.

Often, when leading a charge, Mosby would use a horn used in a foxhunt. His guerrilla warfare was mainly in Virginia’s Loudoun and Fauquier counties, from Aldie to the Shenandoah Valley, an area of many foxhunts. Today, Route 50 runs up the middle of his territory, with the terrain and many buildings the same that Mosby viewed as he was driving the Union forces toward oblivion.

In nearly all engagements, he was greatly outnumbered. The Mosby campaign lasted 28 months, but in that time he drove those Yankees mad. He would attack without warning and quickly disappear. This enraged the North.

His reputation grew. There was one close encounter when he faked his death by smearing his blood from a wound. He was effective in this, for the Union forces left him for dead. After his recovery, he suddenly appeared on the battlefield and once again the federals had to admit that he was truly the “Gray (the color of his uniform) Ghost.”

As a young man, he was fascinated by the guerrilla tactics of Francis Marion, the “Swamp Fox” of South Carolina during the American Revolutionary War. He applied Marion’s tactics to Abe Lincoln’s War. After the war, Mosby was a lawyer in California for Leland Stanford (Stanford University), president of the Southern Pacific Railroad. While in California he would visit friends, i.e., the Patton family. Their young son George S. and he would go to the beach, and the colonel would tell him stories of his exploits as a guerrilla fighter. Years later, General George S. Patton, Jr. became a guerrilla fighter using tanks instead of rangers. Thus, three great American heroes—Francis Marion, John Mosby and George Patton—became related; from the Revolutionary War, to Lincoln’s War, to World War II with Mosby right in the middle. There was always a certain destiny to John Singleton Mosby.

Softcover, 262 pages, $25

Because of his size, he was subject when young to being bullied. This came to a head while a student at Virginia University (UVA), when the campus bully, George Turpin, was angered at fellow student Mosby when some musicians played for Mosby’s party instead of Turpin’s. As was his modus operandi, Turpin would verbally threaten to beat one up at the next encounter. In one case, he nearly killed a fellow student. Mosby, not one to back down, replied to his threat, initially accepting the beating that would follow but this time he packed an old pepperbox pistol for the confrontation.

When Turpin rushed him, Mosby shot him in the neck, which reflected his sense of justice as even the judge later acknowledged. Turpin recovered, Mosby served nine months in jail, was fined $500, and later pardoned by the governor.

At first, Mosby told a friend that he would fight for the Union. But after President Lincoln called up 75,000 volunteers to invade the South, he became a true Southerner. When the vote came for secession in Fauquier County, Virginia, there were only four votes not to secede.

A famous and glamorous and classic example of guerrilla warfare was when Mosby, on March 8, 1863, at Fairfax Court House, captured Brigadier General Edwin H. Stoughton, a West Point graduate, from a prominent family in Vermont. As Mosby awoke him out of bed, the general angrily shouted, “Do you know who I am?”

Mosby replied: “I reckon I do, General. Did you ever hear of Mosby?” “Yes! Have you caught him?” asked the general. “No, but he has caught you,” answered Mosby.

He had captured a brigadier general, 30 men and 58 horses, and all without firing a shot or losing a man. And all of this was done among 3,500 federals. With the odds that great, to many, it appeared he might have had some help from above.

Another of his daring experiences was his escape from the feds at the Hathaway house. Somehow the Yankees got word that Mosby was visiting the Hathaways. After surrounding the house at midnight, the feds rudely knocked on the door of the house, built some three years earlier. They entered the home in search of Mosby. Knocking on all the bedroom doors upstairs, a lieutenant came upon Pauline and John’s bedroom.

Pauline was three months pregnant with John S. Jr., but her demeanor was enough that it allowed John to climb out the window and onto a limb of a large walnut tree, staying there for some eight hours on that warm summer night of June 8, 1863. In spite of the fact that his spurs were found in the bedroom and his horse was discovered, Mosby never was. In the providence of God perhaps, their bedroom was conveniently located by that famous branch.

One of the advantages of being a guerrilla was that the spoils from victory went to the guerrilla. In his 28 months of guerrilla fighting, Mosby and his rangers captured over 3,500 horses and mules and a great number of weapons and were responsible for over 2,900 killed, wounded or captured Union troops. Mosby would award the best horses captured to those who demonstrated great bravery. The going rate in 1863 was $110 for a cavalry horse, $12 or more for a revolver and about $10 for a rifle. So, a ranger could earn more than $132 by capturing one Union cavalryman—which was more than a year’s pay for a private. Often Mosby was paid in gold.

One of the easiest sources of spoils was when they captured a sutler (a civilian who sells supplies to the war machine). This was one of the more pleasurable events in the life of a ranger, as they shared the spoils, which often included a variety of items. On a rare occasion, Mosby would participate in sharing the spoils and the celebration that went with it.

One of the more impressive raids was when the rangers derailed a train, blew up the boiler with a large weapon they had captured and took much spoils, including $174,000 cash. Though his rangers insisted he take his share, Mosby refused. The men then took up a collection of $10,000 and gave it to Pauline. He then returned it to the troops as a Christmas present, and in return they gave him a prize horse, named Coquette, that had been much admired earlier. Mosby had the integrity of a George Washington, ethics that are completely contrary to what is in D.C. today.

America’s War Between the States was one of the cruelest wars in history, with much bloodshed, tears and heartache. Over 625,000 men and 1.5 million horses were killed.

After Mosby greatly embarrassed General Philip Sheridan in his “Wagon Raid” of August 13, 1864 in and around Berryville, Virginia, Sheridan suffered great loss of wagons and their supplies, and the desire to flush out Mosby increased. This resulted in the “Burning Raid” of November, 1864 when Sheridan set up a “hunter-killer team” of 100 men under the leadership of Captain Richard Blazer, with one mission, which was to kill or capture Mosby and his rangers.

The Union troops went up the valley using the terror tactic of mass destruction of civilian property (homes and barns), crops and livestock and the looting of private valuables. Mosby and his rangers were not flushed out.

This cruel tactic was once again used by the Union forces when General William Tecumseh Sherman catastrophically marched to the sea, burning Atlanta on the way.

Mosby was involved in the First Battle of Manassas (Bull Run), and his exploits ended after General Lee surrendered on April 9, 1865, at Appomattox Court House. Mosby never surrendered, but disbanded the 43rd Battalion at Salem (now Marshall) Virginia.

He read this farewell address to his men:

Soldiers, I have summoned you together for the last time. The vision we have cherished for a free and independent country has vanished and that country is now the spoil of a conqueror. I disband your organization in preference to surrendering it to our enemies. I am no longer your commander. After an association of more than two eventful years, I part from you with a just pride in the fame of your achievements and grateful recollections of your generous kindness to myself. And now at this moment of bidding you a final adieu, accept the assurance of my unchanging confidence and regard.

Farewell.

Colonel John S. Mosby, CSA, 43rd Battalion Virginia Cavalry

1 Comment on Will This Book’s Cover Be Outlawed?: The Uncensored Memoirs of One of the Greatest Cavalry Guerrillas in U.S. History