CIA dirty tricks against Iranian democracy led to Islamic fundamentalist revolution.

By S.T. Patrick

“Do you believe in miracles?!” Al Michaels screamed as the ragtag team of amateur American hockey players defeated the dominant Russians 4-3 at the 1980 Winter Olympics in Lake Placid, N.Y. The Russians hadn’t lost a game in Olympic play since 1968. Sports Illustrated named the “Miracle on Ice,” the top sports moment of the 20th century. In isolation, the Cold War-soaked victory was a symbolic moment of great exuberance for Americans. We were that “shining city upon a hill.” Yet, like any other historical benchmark, there is context. Even as the national anthem played and the Americans received their medals on home ice after an anti-climactic gold medal win over Finland, halfway around the globe existed a stark reminder that the world is a much more nuanced place.

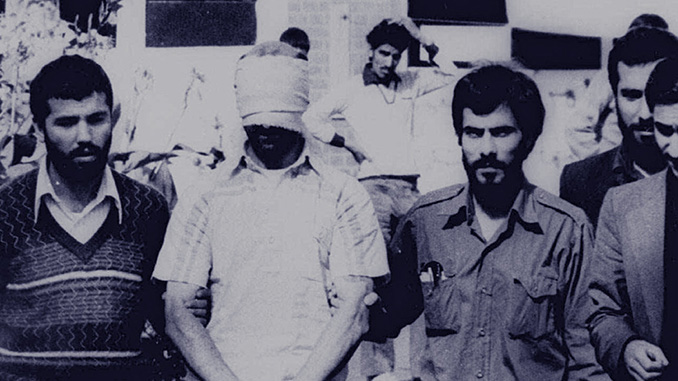

Feb. 22, 1980, the evening of the Miracle on Ice, had marked 110 days since 52 American diplomats and citizens had been taken hostage in Tehran. Iranian college students representing the Ayatollah Khomeini’s Iranian Revolution had overtaken the U.S. embassy in Iran’s capital city. While President Jimmy Carter called it “an act of blackmail” and described the hostages as victims of “terrorism and anarchy,” the students believed they were rightly responding to decades of undue influence into Iranian politics by Western intelligence agencies.

In 1953, the CIA and its British allies overthrew Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadeq in a coup supported by Iranian royalists and Western petroleum companies.* Mossadeq had led a general strike on behalf of Iran’s poorest citizens and the country’s parliament, demanding a percentage of Britain’s Anglo-Iranian Oil Company revenues in Iran. The British and the Americans supported Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, who became the last shah (emperor) of Iran. Quickly, the Shah appointed himself the absolute monarch of Iran and ruled with a bloody, iron fist until he was overthrown in 1979.

In 1953, the CIA and its British allies overthrew Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadeq in a coup supported by Iranian royalists and Western petroleum companies.* Mossadeq had led a general strike on behalf of Iran’s poorest citizens and the country’s parliament, demanding a percentage of Britain’s Anglo-Iranian Oil Company revenues in Iran. The British and the Americans supported Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, who became the last shah (emperor) of Iran. Quickly, the Shah appointed himself the absolute monarch of Iran and ruled with a bloody, iron fist until he was overthrown in 1979.

The U.S. had reason to believe they could work with Khomeini, who had returned to Iran from exile in France. Carter tried a minor amount of diplomacy, a sticky venture lacking legitimacy since the Americans had propped up the Shah for three decades. It was all for naught when Carter allowed the Shah to enter the New York Hospital-Cornell Medical Center for treatment of lymphoma.

Carter’s State Department had discouraged the Shah from even making the request to the administration, but pressure mounted from all political persuasions. Henry Kissinger threatened Carter to allow the Shah in or he would not publicly support the SALT (Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty) talks. Council on Foreign Relations founder David Rockefeller also pressured Carter, though surely through his Trilateral Commission cofounder, Carter’s national security advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski.

Carter relented and allowed the Shah to seek treatment in New York on Oct. 22, 1979. Protests intensified in Iran, as students believed the Americans would attempt another coup aimed at reinstalling the Shah to power, and students took the embassy and the hostages on Nov. 4, 1979.

Nine days after the hostages were taken, former California Gov. Ronald Reagan took to national television to announce that he would seek the presidency in 1980. Anathema to his hyper-positive “Morning in America” campaign in 1984, Reagan in 1980 said that America had been “naïve, sometimes wrong” in its policies. When speaking of Canada and Mexico, he said, “It is time we stopped thinking of our nearest neighbors as foreigners.” While Americans would soon realize what the Reagan campaign would be, on this night there was a reasonable level of uncertainty, and these were troubled times.

In January 1980, CBS newsman Walter Cronkite began opening each episode of his nightly news program by counting how many days the Americans had been in captivity. Carter engaged in multiple rounds of secret negotiations, but Khomeini nixed each of them after the president had agreed to minor concessions. The pressure to do something weighed heavily on the White House, resulting in a failed rescue attempt in April 1980, a helicopter crash that killed eight servicemen and injured others.

The Shah died on Feb. 20, 1980 as tension over the crisis continued to be the dominant topic during the entirety of the 1980 campaign for president. The Iranian Hostage Crisis lasted 444 days and ended when the Algiers Declaration was signed—on Jan. 20, 1981, Reagan’s inauguration day. Though elated with the result, skeptical observers commented on the convenience of the timing of Reagan’s first great policy victory. Rumors of an “October Surprise” abound. Did the Reagan team covertly secure and then delay the release of the hostages until Inauguration Day? Researchers Robert Parry, Barbara Honegger, and Gary Sick all believed so, though they disagreed about the level of involvement at the highest levels.

The hostage crisis was the historical dagger to the heart of the Carter presidency. He had accurately assessed the country was in a “malaise,” but failed to recognize his role in its creation. On Feb. 20, 1980, he announced that the Russians had not met a demand to withdraw all troops from Afghanistan, and, therefore, the U.S. would not be sending its athletes to the 1980 Summer Olympics in Moscow. Americans could have used a temporary lift that summer, but there would be no more Olympic miracles as the calendar kept turning for American hostages, captive in a strange land, and for a president bound by a situation he couldn’t resolve.

——

*The CIA in Iran: The 1953 Coup and the Origins of the U.S.-Iran Divide can be purchased for $15 plus $4 S&H in the U.S. from AFP, 117 La Grange Avenue, La Plata, MD 20646./ Call 1-888-699-6397 toll free to charge. Mon.-Thu. 9-5 ET. See also www.AmericanFreePress.net.

S.T. Patrick holds degrees in both journalism and social studies education. He spent 10 years as an educator and now hosts the “Midnight Writer News Show.” His email is [email protected]. He is also an occasional contributor to TBR history magazine and the current managing editor of Deep Truth Journal (DTJ), a new conspiracy-focused publication available from the AFP Online Store.