By S.T. Patrick

When the archetypes of a Hollywood western become the mainstream narrative of the American mainstream media, real history suffers. Neither the writers and directors who are supposed to be reflecting it, nor the mainstream media and analysts who are supposed to be accurately reporting it, are doing history or anyone a favor by slanting it, sugarcoating it or wrapping it in red, white and blue. This was precisely the case with Afghanistan and the movie Charlie Wilson’s War.

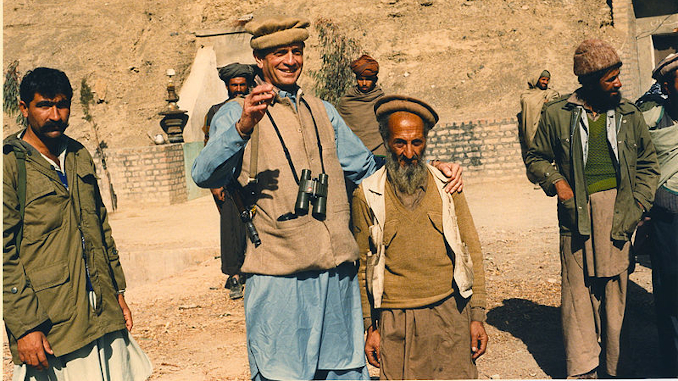

The story of Rep. Charlie Wilson (D-Texas), dramatically portrayed in the 2007 Tom Hanks film Charlie Wilson’s War, is told as a battle between the white hats, the “freedom fighters” of the Mujahideen, and the “black hats,” the invading Soviet occupiers. Though the film, and the 2003 George Crile III book from which it is based, originated well beyond the Reagan era, the plotlines are filled with as many 1980s Cold War tropes as Rocky IV, the Rambo films, or any James Bond film. The Americans, of course, not only finance the freedom fighters. Rather, they are the intellectual and ideological freedom fighters behind them.

Wilson, a maverick Texas congressman, warms up to and then falls in love with the idea of backing the Mujahideen fighters in their nationalistic struggle against the occupying Soviets after being convinced by and falling in love with Texas oil woman Joanne Herring (Julia Roberts in the film), a fierce anti-communist. In true film fashion, you’re supposed to see the parallels of the mind following the heart, or vice versa. It’s the rebirth of Charlie Wilson. And it would be a pleasant story if it were true. A recently found 2003 document tells us that it is not.

On a research visit to the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library in Simi Valley, Calif. in 2003, Robert Parry came across a fascinating document in the files of former CIA propaganda chief Walter Raymond Jr. In the 1980s, at the height of the Soviet-Afghan War, Raymond, from his office in the National Security Council, was tasked with marketing the U.S. interventions in Afghanistan and Central America. There is a note in Raymond’s file from National Security Adviser Robert “Bud” McFarlane.

The letter from McFarlane to Raymond read, “Walt, Go see Charlie Wilson. Seek to bring him into circle as [discreet] Hill connection. He can be very helpful in getting money. —M.”

As Congress began tightening the coffers on spending in Nicaragua, going so far as to pass the Boland Amendment banning the financing of the Contras against the Sandanistas, the financing of the Mujahideen in Afghanistan expanded. Raymond’s efforts to corral supporters on Capitol Hill and beyond also intensified.

Much of this was declassified in 1987, when many of the Iran-Contra papers were released. To get three Republican moderates to sign on to the official Democratic “Iran-Contra Report,” the Democratic leadership agreed to remove a chapter of the report that dealt with the CIA’s domestic propaganda role in Afghanistan and Central America.

The withdrawn chapter, summarized by Parry, dealt with the fact that “one of the CIA’s most senior specialists, sent to the National Security Council by Bill Casey, to create and coordinate an inter-agency public-diplomacy mechanism [which] did what a covert CIA operation in a foreign country might do. [It] attempted to manipulate the media, the Congress, and public opinion to support the Reagan administration’s policies.”

One of Raymond’s ill-conceived plans was to encourage members of the Soviet military to defect to the Mujahideen. They would then be flown directly to Washington, D.C. where they would hold a press conference and denounce communism. The problem with the plan was that almost any Soviet soldier who came into the custody of the U.S.-backed Afghan Mujahideen was tortured, raped, killed or a combination of the three. In American terms, they were subject to “extraordinary rendition.”

The truth of Wilson’s involvement, as history can be, is complex and nuanced. “The newly discovered document about bringing Charlie Wilson into the White House ‘circle as discreet Hill connection,’” Parry wrote, “suggests that even the impression that it was ‘Charlie Wilson’s war’ may have been more illusion than reality. Though Wilson surely became a true believer in the CIA’s largest covert action of the Cold War, Reagan’s White House team appears to have viewed him as a useful Democratic front man who would be ‘very helpful in getting money’.” Rather than being the mover and shaker of the operation in Congress, Wilson was the one moved and shaken.

The underreported and under-investigated portion of the story is the role of Herring. The Houston socialite was a childhood friend of James Baker III, chief of staff under Reagan and George H.W. Bush and secretary of state under Bush. Herring was also close to the president of Pakistan, Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq. Herring received the Jinnah Medal from Zia-ul-Haq, one of Pakistan’s highest honors. It was Herring who introduced Wilson to Zia, who later died in a mysterious plane crash in August 1988. Also on the plane with Zia were ISI Director Akhtar Abdur Rahman, U.S. Ambassador to Pakistan Arnold Raphel, and other Pakistani and U.S. officials. The ISI is the Pakistani version of the CIA. To think Herring brushed against Wilson for romantic reasons is alluring but seems unlikely. As the American notably closest to the ISI-linked Pakistani president, and as someone doing the bidding for the Reagan anti-communist incursions on the social scene, Herring, it appears, was being used for the purposes of the military-industrial complex as much as Wilson would be.

Then again, “based on a true story” never meant a film was, factually, a true story. It simply means that there are some likenesses, some similarities, and maybe even some characters that share something in common with something that did happen. That is not supposed to be the case with the news media charged with reporting what did happen regardless of nuance or complexity. If one believes America has spent a century being “dumbed down,” Hollywood and the mainstream media have been willing and witting partners, equally, with education in accomplishing this.

Charlie Wilson’s War was as much myth as it was history. And that would have been okay, as that is what is now expected of Hollywood productions that are vehicles for its biggest stars. Yet, Washington is not supposed to follow the myths into decades of bad policy.

History is not making truths of myths as much as it is making myths of truths. We can only hope that the impetus for the next disastrous decades-long U.S. occupation of a foreign nation is not an extension of Cold War or “War on Terror” mythologies, as well.