• Sequel to Pulitzer Prize-winning classic that glorified racial integration leaves millions horrified by white protagonist’s 180° turnaround.

By Dave Gahary —

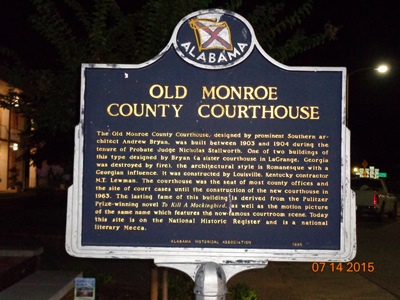

MONROEVILLE, Alabama—Hundreds of Southerners happily lined up at the Ol’ Curiosities & Book Shoppe in this southeastern Alabama town after midnight for the follow-up novel from Nelle Harper Lee, 55 years after To Kill A Mockingbird transfixed Americans, who fell in love with the main fictional character, Atticus Finch.

Finch, modeled after Lee’s own father, Amasa Coleman Lee, who married Frances Finch in 1910, settled in Monroeville in 1912 and died there in 1962. He was a lawyer, member of the Alabama House of Representatives, and editor of a local newspaper. In the book he defends a black man from a murder charge he clearly didn’t commit, and teaches racial tolerance to the prejudiced locals in the fictional town of Maycomb.

Finch “was a moral hero for many readers and as a model of integrity for lawyers.” As one critic put it, the novel’s impact by writing, “In the twentieth century, To Kill a Mockingbird is probably the most widely read book dealing with race in America, and its protagonist, Atticus Finch, the most enduring fictional image of racial heroism.” The novel was so popular that many parents named their children Atticus, and even young people today remain fascinated by the tale.

Mockingbird, set in the late 1930s and published in 1960, was an instant success, and has become a classic of modern American literature, “more popular than even the Bible in numerous polls.” “The plot and characters are loosely based on the author’s observations of her family and neighbors, as well as on an event that occurred near her hometown in 1936, when she was 10 years old.”

Now, with the sequel released on Tuesday, July 14, Go Set a Watchman, millions of people the world over, who vicariously lived through the fictional Atticus, are in for a big surprise: Atticus isn’t the integrationist America fell in love with. He’s evolved into a hard-core segregationist.

In real life, Mr. Lee was a practical Southern gentleman. After the Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court decision in 1954, which forced whites to share their schools with blacks, he resisted school integration, and “clashed with his Methodist pastor, who was preaching about social justice.”

“Do you want Negroes by the carload in our schools and churches and theaters? Do you want them in our world?” Atticus asks his daughter in the new book.

In another part of the book, Atticus explains to his daughter, Scout, the realities of the new South, as it relates to black lawyers and the federal government, which also sheds light on how this affects legal cases today.

“Scout, you probably don’t know it, but the NAACP-paid lawyers are standing around like buzzards down here waiting for things like this to happen—”

“You mean colored lawyers?”

Atticus nodded. “Yep. We’ve got three or four in the state now. They’re mostly in Birmingham and places like that, but circuit by circuit they watch and wait, just for some felony committed by a Negro against a white person—you’d be surprised how quick they find out—in they come and . . . well, in terms you can understand, they demand Negroes on the juries in such cases. They subpoena the jury commissioners, they ask the judge to step down, they raise every legal trick in their books—and they have ‘em aplenty—they try to force the judge into error. Above all else they try to get the case into a Federal court where they know the cards are stacked in their favor.”

In light of the sour race relations infecting the country, due mostly to the cues taken from America’s first black president, many people are now being forced to take a second look at how they view their African-American neighbors. Atticus made it acceptable for whites to accept blacks as equals. Now, he’s turning that entire lovey-dovey, smile on your brother, can’t we all just get along, have a Coke and a smile nonsense on its head.

Lee, who went by Harper Lee, because she felt her first name would confuse people (it’s “Ellen” backwards), wrote her first book, Watchman, which was set in the mid-1950s, but her editor “persuaded her to rework some of the material, in effect transforming it to Mockingbird, after two and a half years. Her editorial team warned her she would sell just a few thousand copies. Mockingbird has so far sold more than 40 million copies. Lee, 89, is expected to spend Tuesday at the assisted living facility where she lives in Monroeville.

There are those who doubt Lee ever wrote Mockingbird, AFP’s Victor Thorn in that camp as well.

“It’s been a case of speculation for decades now,” Thorn said. “One of the big questions is, she writes a best-selling novel, turns into a blockbuster Hollywood movie, and she never writes anything in the decades after that. She was childhood friends with Truman Capote, and it’s been speculated that he was the one who wrote To Kill a Mockingbird. To me it’s one of the biggest literary mysteries up there, right up there with Shakespeare.”

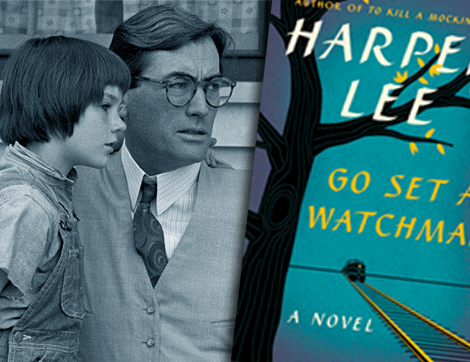

Lines at the bookstore were still thick after 1:30 a.m., with a character resembling and dressing like the actor Gregory Peck, who played Atticus in the motion picture. An email sent from this writer to the bookstore today asked how many books were ordered and how many sold, in the town of around 6,500 residents.

“In total honesty, we’ve been too busy to compile an exact count,” the email stated. “The shoppe has ordered OVER 10,000 from our supplier, and our best estimate is that we’ve sold 8,500 copies to our customers as of this morning.”

Dave Gahary, a former submariner in the U.S. Navy, is the host of AFP’s ‘Underground Interview’ series.

Be sure to check out all of AFP’s free audio interviews. You’ll find them on the HOME PAGE, in the ARCHIVES & in the AUDIO section.